Nonviolent Communication

Find out what Nonviolent Communication is and why we think it’s such an important tool for supporting children at Wildwood Nature School.

What is Nonviolent Communication (NVC)?

Nonviolent Communication is a communication tool that was created by the American psychologist Marshall B. Rosenberg as a result of his work with civil rights activists in the 1960s. NVC has been used to promote peace, reconciliation, and conflict resolution across the world in places such as Rwanda, Serbia and the Middle East.

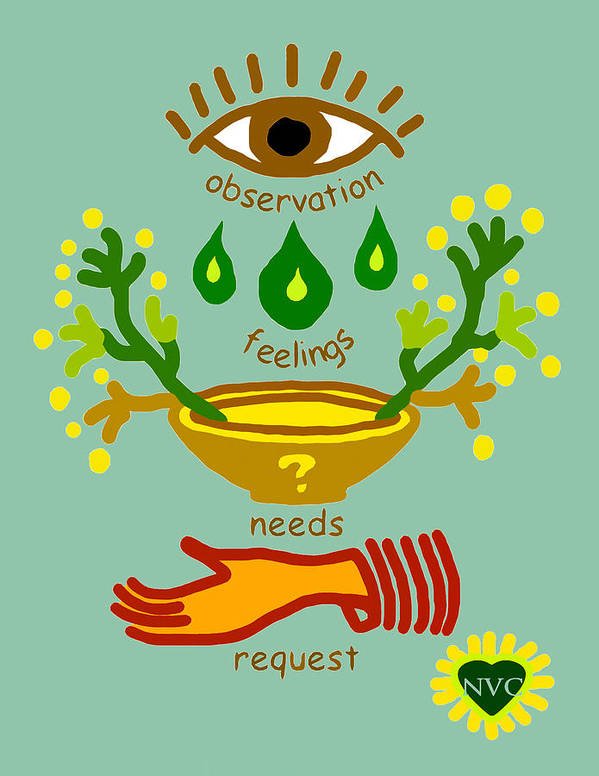

Rosenberg describes NVC as a “language of the heart.” At its core, NVC supports the development of an interdependent community that works to meet the needs of everybody and tries to make life more wonderful for everyone. He explains, “the goal of Nonviolent Communication is not to get what we want but to make a human connection that will result in everyone getting their needs met.” Rosenberg’s work involves getting people to connect with their feelings in each moment, recognising the unmet need which is causing that feeling, and expressing those feelings and needs to others. He emphasises moving away from blame, shame and moralistic judgements of right/wrong and good/bad. The aim is to be able to observe without judgement, express feelings, needs and requests, and to be able to empathise with others as they express their observations, feelings, needs and requests.

This is much easier said than done in a world where interpretation, criticism, diagnoses, judgements of others, blame and shame are the norm. Most of the time we’re not even aware that we’re interpreting, judging and blaming others. NVC is a powerful tool for developing self-awareness, as well as building relationships with others, because it shows us that at the root of so many of our feelings are unmet needs. Normally, when we’re in conflict with someone else, we immediately assume that our difficult feelings arise because of the other person’s actions or words. But Rosenberg explains that,

“Nonviolent Communication heightens our awareness that what others say and do may be the stimulus for our feelings, but are never the cause. Our feelings result from whether our needs are being met or not.”

Rosenberg also draws our attention to the fact that so often, even when we say, “I feel…” we often follow that with words such as “that, like, as if, you, he, she, they” which actually counteracts the very meaning of the words “I feel” because it places the origin of the feeling outside of ourselves. Words such as betrayed, manipulated, inferior, misunderstood, used, criticised are not feelings; they are false feelings. The image below shows the wide range of feelings and emotions that are best to use when trying to communicate feelings.

From The Junto Institute

The use of the non-judgemental language of observation - e.g. “I noticed you arrived 30 minutes after our agreed-upon meeting time”, rather than, “You’re always late” - removes the blaming, shaming and judgement that can often create defensiveness and disconnection. The next steps in NVC are about expressing our feelings and needs - e.g. “I felt worried about you and now I’m a bit frustrated. I value reliability and punctuality because it helps me feel respected and allows us to make the most of our time together.” When the focus is on the speaker’s feelings and needs, the person receiving this can actually hear it because they don’t feel as if they’re being blamed or attacked. The final step is to make a specific and realistic request, rather than a demand. One that the other person must feel free to say no to, otherwise it’s not truly a request. For example, “Would you be willing to let me know in advance if you expect to be late in the future? It would really help me feel more at ease and manage my time better.” It also needs to be a positive request i.e. what the other person can do, not what they should not do e.g. “Please never be late again” (which is also vague and unrealistic).

“This is a language for those of us who want people to say ‘yes’ to our requests only if they can do so willingly and compassionately. Since the objective of Nonviolent Communication is to create the quality of connection necessary for everyone’s needs to get met, when we speak it we are not simply trying to get people to do what we want. And when people learn to trust that our commitment is to the quality of the relationship – to honesty and empathy – and that our goal is for everyone’s needs to be fulfilled, they can trust that our requests are requests and not demands.”

What NVC does is create an environment of empathy and understanding, where connections are actually deepened, rather than strained, by conflicts and issues. It also teaches us empathy because the last part of NVC involves being able to reflect back to the other person their observations, feelings, needs and requests to ensure that they’ve been fully understood. This requires a whole-body, present listening that aims to move past trying to analyse what the other person is saying and just truly receive it. It’s an incredibly powerful mode of communication and one that fits perfectly with Wildwood Nature School’s ethos and commitment to building a community where each child, teacher and parent can feel seen and respected.

Understanding needs

Alice Sheldon, an NVC trainer, author, former teacher and barrister, with an MA in Psychology and Neuroscience, founded Needs Understanding to help facilitate parents, teams and organisations to better understand themselves and others. She expands upon Rosenberg’s concept of unmet needs in a beautiful and very relatable way. Her very aptly-titled book, Why weren’t we taught THIS at school? gets at the core of what we are trying to teach at Wildwood Nature School: the very essence of understanding ourselves and how to relate to others compassionately.

“Needs Understanding…[is] based on one core idea: that everything we say or do is an attempt to meet our underlying human needs….

Principle 1: Our behaviour is always an attempt to meet our needs.

Principle 2: Our world works best when our chosen strategies take care of everyone’s needs.”

Below shows a list of the universal needs often referred to in NVC (Sheldon has added a few more to this list which can be downloaded from her website):

Sheldon explains that these needs go beyond just survival, and are actually what we need to thrive in life. She suggests that everyone has a few “fingerprint needs”:

“Our fingerprint needs are usually related to how well (or not) our caregivers met our needs when we were children, regardless of how loving a home we may have grown up in. When something in our adult world touches on one of them, it becomes an overriding priority for us to grab onto whatever it is that we’re not getting. We lurch into the same survival mode in which we lived when we were three or four years old and depended on our caregivers for everything. The situations in which we overreact to a fingerprint need not being met are also those that tend to cause us the most issues in our close relationships.”

Those arguments that we have over and over again with our partners? Normally a fingerprint need that’s not being met. Experiencing the same frustrations with a manager in every job? Again, it’s likely to be an unmet fingerprint need.

“We perceive unmet fingerprint needs as being a threat to our very existence, causing us to leap inappropriately into survival mode. The pre-frontal cortex part of our brain shuts down, making us incapable of rational thought, and our limbic brain – the seat of our emotions – takes over.”

When we can identify these core unmet needs in ourselves, we can start to change those entrenched patterns that cause difficulty in our lives. When we express that a really important need is not being met to a partner, friend or boss, it’s normally met with a softening, along with greater understanding, connection, and most likely, a new way to move forward. It’s vital that as the most important adults in children’s lives - parents and teachers - we model how to be self-aware, express ourselves compassionately, and find ways to meet our own needs and those of the people around us.

“If we can start to understand that our feelings are vulnerable messengers about our needs, we can accept them, make sense of what they’re telling us, and act on them with awareness. Rightly understood, our feelings are a resource rather than a distraction that gets in the way. They’re an indicator of what’s important to us in any given moment.”

Sheldon discusses empathy as being absolutely at the heart of compassionate communication. She describes empathy as:

“my understanding of your experience and feelings, with full acceptance and without judgement…[or] getting you so you know you’ve been got….Full empathy involves developing a felt sense of what it’s like to walk in their shoes and see the world through their eyes, as if you were them.”

Being able to offer empathy to someone else helps them to feel secure and safe enough to want to find solutions, build connection and to compromise if necessary in order to get everyone’s needs met.

In her work on Needs Understanding, Sheldon analyses the benefits of appreciation and celebration vs. rewards and praise. There’s a growing body of research that shows how detrimental praise and rewards can be on children’s self-esteem, self-worth and motivation (see Alfie Kohn and Carol Dweck).

“Whether praise and rewards are bestowed by parents, managers, or others in positions of authority, they don’t tend to lead to relationships built on trust, or foster closer connections. More often than not, they’re well-meaning attempts to manipulate our behaviour so that it conforms to what other people want. Even more harmfully, they can encourage us to change what we do so that we’ll win a reward for it, rather than giving us the freedom to act from a genuine desire to do what meets our needs and those of the people around us.”

Praise and rewards can lead to a dangerous dependence on external validation for our sense of worth and can take away from our ability to value ourselves. Sheldon points out that praise and rewards always have a power imbalance. She explains that you wouldn’t praise or reward a friend if they’d just got engaged, or got a promotion; you’d celebrate with them. You’d join in with their joy. This links back to something Rosenberg discusses - the concept of “power-with” rather than “power-over”. When we have power over another person, they might do what we want them to, but this comes from a place of fear or seeking rewards. Whereas when we share power with others, we can support them to find motivation from within; which is much more valuable and long-lasting. At Wildwood Nature School, we create a culture of respect and we celebrate with children rather than offering them meaningless praise and rewards.

Making amends through genuine apology and expressing regret and sorrow is another element of Sheldon’s compassionate communication toolset. What NVC and Needs Understanding teach us is radical self-responsibility: taking responsibility for our own feelings and equally, for our mistakes. She explains that so often when there’s been an incident, the response is often either denial and defensiveness or overwhelming guilt and grovelling, and needing the other person to make us feel good about ourselves again. When we approach this from a different perspective, we can choose to make amends by saying sorry empathically (without buts or explanations), owning our mistakes, and putting in place whatever’s needed to move forward and repair the relationship. There’s no need for guilt, which only tends to damage relationships.

How does NVC relate to children and education?

NVC might seem like quite a complicated concept but Marshall Rosenberg absolutely intended for it to be taught to young children in schools. And what a beautiful gift to give to children - to teach them how to be aware of their own emotions, feelings and needs and to have the skills and confidence to express those, even in times of conflict, to get their needs met. Imagine if all of the adults in the world had learned this at school? The world might look very different….

Rosenberg and his NVC facilitators have led training in thousands of schools around the world. When schools use this approach, he refers to it as “life-enriching education.”

“Life-Enriching Education is based on the premise that the relationship between teachers and students, the relationships of students with one another, and the relationships of students to what they are learning are equally important in preparing students for the future…Children need far more than basic skills in reading, writing and math[s], as important as those might be. Children also need to learn how to think for themselves, how to find the meaning in what they learn, and how to work and live together.”

He explains that there are so many forms of violence prevalent in schools, including:

Punishment;

Rewards;

Guilt - when teachers make children believe they’re responsible for the teacher’s feelings e.g. “You make me angry when you interrupt me;”

Shame - any label that implies wrongness;

“Amrssprache” or “bureaucratese” – what the Nazis used to justify their actions e.g. “Superior’s orders. Company policy. It’s the law.” This is such a common reasoning in mainstream schools - leaders say no to ideas that will support children’s well-being because of bureaucratic, logistical or governmental restrictions. He even explains that our language can deny responsibility for choice with words such as “have to, can’t, should, must, ought.”

In life-enriching, nonviolent education, children are equal participants with the teachers in establishing rules and boundaries. When children see that certain guidelines need to be put in place to protect and keep everyone safe, and they’ve helped define them, they’re much more likely to respect them. It helps to develop self-discipline rather than obedience. Furthermore, when they understand that the goal is always ensuring the well-being of each member of the community and meeting everyone’s needs, and that this is done through honest and compassionate communication, a community of deep connection and respect can be built. Through regular class meetings at Wildwood Nature School, children get to have a voice, be a part of the decision-making process, question why we do things in certain ways, and genuinely make a difference. It’s about educating “this and future generations of children to create organisations whose goal is to meet human needs, to make life more wonderful for themselves and each other.”

This concept carries through to their learning as well. We encourage children to direct their own learning as much as possible so that it’s meaningful to them. Teachers at Wildwood support children to choose their area of learning, set their own learning goals, decide how they want to research, carry out and present their work, and how to assess their learning and understanding against the goals they set for themselves. We strive to create an interdependent learning community where children care about each other’s learning as well as their own. This might mean children teach other children in areas where they’ve decided to focus their efforts.

“In a classroom where everyone has a different set of learning objectives, where there is no established hierarchy of achievement, it is quite possible for a student to be capable of teaching in one area but in need of instruction in another, and comfortably both offering and asking for help.”

Why do we call it Giraffe language?

Rosenberg and his colleagues realised that Nonviolent Communication was quite a mouthful to say for young children. So when referring to NVC with children he calls it “Giraffe language.” This is because giraffes are the land animal with the largest heart and NVC is a language of the heart. He also uses the concept of the “jackal” to represent:

“that part of ourselves that thinks, speaks, or acts in ways that disconnect us from our awareness of our feelings and needs, as well as the feelings and needs of others. “Jackal” language makes it very hard for a person who uses it to get the connection they want with others.”

Jackal language uses a lot of blaming, shaming and judgement, as well as some of the false feelings described above (e.g. betrayed, unappreciated, misunderstood - you can download a list of false feelings from Alice Sheldon’s website). Rosenberg explains that it’s common in our society to have “jackal ears” on, so that even when someone is speaking from the heart, we hear criticism and judgement. His training is about teaching children not only to speak from the heart with giraffe language, but to put on their “giraffe ears” so that they can hear another person’s needs and feelings even when they’re using “jackal language.” While this can be so difficult, it’s the surest way to ensure connection and getting everybody’s needs met.

At Wildwood Nature School, teachers first and foremost model using giraffe language and ears in their interactions with the children, with each other and with the families in the school community. We also explicitly teach children about giraffe and jackal language, how to feel and name their feelings, how to relate their feelings to unmet needs, and how to follow the NVC steps to conflict resolution (see below). This takes time and practice, but when it’s used every day throughout a child’s primary school experience, the hope is that they come out into the world able to get their needs met and meet others’ needs with compassion.

“NVC is interested in learning that’s motivated by reverence for life, by a desire to learn skills, to better contribute to our own well-being and the well-being of others….NVC is a way of keeping our consciousness tuned in moment by moment to the beauty within others and ourselves.”

What are the steps to conflict resolution using NVC?

Conflict resolution can be carried out between the 2 children who have been in conflict, or a mediator (an adult or another child trained in the approach) can be present to state each step, and remind both parties to keep using Giraffe language. Traditional NVC has 4 steps, but at Wildwood Nature School we’ve added in an important first step: coming into the body to ground and regulate the nervous system. We believe that conflict resolution and communicating compassionately can only happen when both parties' nervous systems are regulated. If that’s not the case, it’s best to wait until a time when everyone is calm and ready to communicate.

Below are the Wildwood Nature School guidelines for conflict resolution using Giraffe language:

1. BODY – each child needs to take a moment to come into their bodies and notice what sensations they can feel. Use known strategies to ground and centre e.g.

using the breath or a somatic anchor.

Now, child 1 goes through the following 4 steps while the other child listens empathically – receiving what they are saying without hearing blame or criticism.

2. OBSERVATIONS – What I observe/see/hear/remember/imagine free from my evaluations and judgement that does or does not contribute to my well-being.

“When I see/hear…”

3. FEELINGS – How I feel (emotion or sensation rather than thought) in relation to what I observe.

“I feel…”

4. NEEDS – What I need or value (rather than a preference or a specific action) that causes my feelings.

“…because I need/value…”

5. REQUESTS – clearly requesting that which would enrich my life without demanding. The concrete actions I would like taken.

“Would you be willing to…?”

Child 2 can be invited to reflect back to child 1 that they have understood their observations, feelings, needs and requests (sometimes this can be nonverbally when offering empathy). Child 2 can then state their observations, feelings, needs and requests while child 1 listens and receives empathically and then reflects back their understanding.

Poster by Heidi Hanson

References

Dweck, C.S. (2017) Mindset. Changing the way you think to fulfil your potential. Revised edition. London: Robinson.

Kohn, A. (2006) Beyond Discipline: From compliance to community. 2nd Ed. Alexandria: ASCD.

Rosenberg, M.B. (2003) Life-Enriching Education: Nonviolent Communication helps schools improve performance, reduce conflict, and enhance relationships. Encinitas: PuddleDancer Press.

Rosenberg, M.B. (2005) Teaching Children Compassionately: How students and teachers can succeed with mutual understanding. Encinitas: PuddleDancer Press.

Sheldon, A. (2021) Why weren’t we taught THIS at school? Great Britain: Practical Inspiration Publishing.

The Child Development Project (2003) Ways we want our class to be. Oakland: Developmental Studies Center.